We have friends here in Tahiti who have been looking to buy a house for more than two years. It’s not an easy feat because sometimes the land is embroiled in inheritance disputes, or sometimes the land is too remote to get any water or electricity lines.

I imagine if they had the possibility of just downloading a house they liked that could generate its own electricity and water, I’m sure they’d jump at the opportunity.

So for our friends, and anyone else who’s struggling to find the right house, The Global Tiller looks at 3D-printed houses this week. We examine how far this technology has come and how global its spread is? Will 3D-printed houses resolve our housing crisis once and for all?

The housing crisis looks different in different parts of the world. In Tahiti, it’s mostly the prices skyrocketing. So much so that the French Polynesian government recently passed a bill imposing a 1,000% tax on purchase of land by non-residents and those who’ve only been living here less than 10 years. In Australia, rental properties have become increasingly unaffordable to those making minimum wage. In the US, a shortage of construction workers and delays in materials delivery is contributing to a worsening housing crisis.

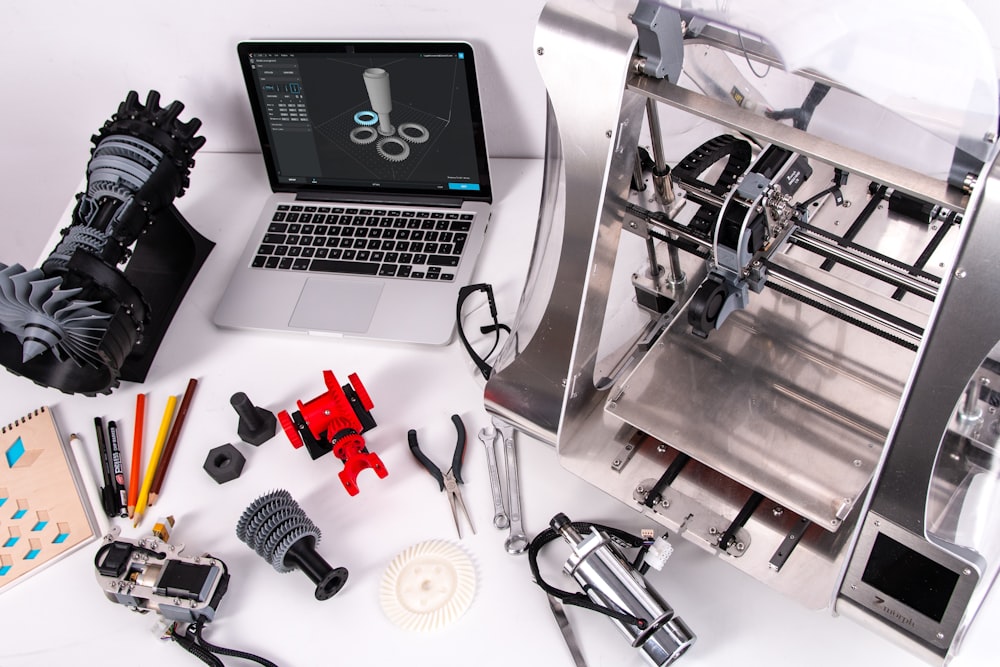

No matter what the cause, the one solution that seems to answer all these problems is 3D construction printing. The way it works is that giant 3D printers are placed on a construction site and they create shapes through a computer-controlled process using concrete, soil, polymers, plastics and other construction materials.

The process is lauded for its efficiency. It requires low level of monitoring and supplies can be lined up ahead of time. It comes, therefore, as no surprise that the largest 3D-printed building in the world in Dubai was built by just three workers and a printer. China built a mansion and an apartment block back in 2015 and Japan has recently succeeded in 3D printing a house in less than 24 hours.

This innovative construction method also boasts of sustainable practices, such as hollow walls that use up less material and offer natural insulation that reduces the need for air-conditioning. But it has potential to become even more environmentally friendly once it moves away from concrete towards more sustainable construction materials, such as raw earth, mud and bamboo composites.

Considering that 3D printing allows digital designs to be literally downloaded as it is, buildings no longer have to conform to conventional shapes and sizes. In fact, these houses may not even have to be connected to the national electricity or water grids as the latest iterations of 3D-printed homes come with solar panels and systems to grab moisture from outside to supply water inside.

As promising as it seems, 3D printed houses still have a long way to go. We need to figure out how they work in high-density areas and how this construction method could be made more affordable to make it accessible for vulnerable sectors. The Australian government is considering a trial run of 3D-printed houses to overcome its housing crisis and 14Trees is trying to do the same in Africa. If successful, this could pave the way for affordable housing in countries with massive slums and homeless populations. Could 3D-printed houses offer solutions in communities on the frontlines of climate change? When cyclones and wildfires wipe out entire villages, could 3D printing come to their aid?

Until next time, take care and stay safe!

Hira - Editor - The Global Tiller

Note: The Global Tiller will not be making its way to your inboxes the next two weeks as I’ll be travelling. If you are a new subscriber to the newsletter, you may want to go back to our past issues and discover other global trends we’ve covered in the past.

Dig deeper

The technology has been touted as a solution to the housing crisis—but how practical are 3D-printed homes for everyday living?

…and now what?

During the height of the pandemic, I remember seeing the community of 3D printers in Tahiti and many other places in the world, getting together to share blueprints of face masks and visors to increase the pace of production and making sure everyone got their PPEs on time given the world shortage.

At that time, I remember thinking that this could be a glimpse of what globalisation could become in the future: not one of capital, not one of centralised power but decentralised (and cheap) production, one based on sharing ideas, on solidarity and the ability to gain locally from the global wisdom of human communities.

As I read about 3D-printed houses, I can’t help but think that this could be the next step in this new idea of globalisation.

You may have come across on social media, as I did, the videos presenting those new houses: in trees, on the ground, made out of this or that material — ideas of new houses and new ways for humans to find shelter sparking everywhere in the world. Inspired by long-lasting local traditions and facing new challenges, human’s creativity is always trying to renew one of the most ancient needs of our species: finding comfort within our homes.

Now let’s try to imagine what the future of housing could be in a world where 3D printing becomes commonplace.

The year is 2052 and you just bought or inherited (as is often the case in Tahiti) a piece of land and you’re planning to build your house. Knowing the dire economic context, you can’t afford a big mortgage so you prefer to start with a small model. You go online, you browse on a dedicated platform (some kind of Pinterest of ready-to-build homes) and find one that attracts your eyes. It’s a smooth design, perfect size, almost the printed-house of your printed-dreams!

You validate the payment through your bio-ID reference and there you go, the blueprint is downloaded onto your phone. You take your e-bike down to the local material provider to show him the blueprint. Based on this, the contractor shows you all the different local resources available to efficiently print your house. Here in Tahiti, it could be concrete made of dead coral (unfortunately, we may have heaps of these in the coming decades), a mix of coconut fibre and our faithful and symbolic Uru tree because an ingenious 3D ink taken from responsibly managed Uru plantations has been invented recently.

The contractor gives you an estimate of the cost of the materials, you sign the document and off you go. In two weeks’ time you’ll have your house. And, who knows, in a few years, you’ll come back again to print an extension made out of this new material inspired by volcanic stones: strong, resistant, but porous enough to ease the ventilation of your house, ready to face the new heat waves of the time.

Does it seem real to you? Well it’s not so far fetched and it’s a way to rethink our global collaboration. Printing houses as well as printing masks may just be the first clues of a future globalisation of ideas in which communities pool in their creativity to build together our global homes.

Philippe - Founder & CEO - Pacific Ventury