Would you eat Sonic the Hedgehog’s special edition blue curry?

This image popped up on my Twitter feed a few days ago and the very idea of eating something blue made me nauseous. And I know this food was really repulsive because I was fasting at that time, which normally means anything edible will make me drool.

Thankfully, the blue food movement has nothing to do with this blue curry.

Join us in this week’s The Global Tiller as we take a look at blue food and what the blue food movement is trying to achieve. Which regions are leading the charge and what are some questions that can guide our understanding of sustainable foods?

Blue food is the nutritious and diverse foods that come from our planet’s bodies of water — streams, rivers, lakes, wetlands, seas, and oceans. It can include up to 2,500 different aquatic animals, plants, and even algae.

The case for adopting blue food is made when you look at the numbers in this industry. Two-thirds of blue food consumed by people is produced by small-scale fisheries and aquaculture, and this feeds up to three billion people — making up 20% of their intake of animal protein. Nearly 800 million people rely on blue food systems for their livelihood and half of them are women. So if we want to have a future with healthy, equitable and sustainable food systems, we may have hit a jackpot.

And that’s the reason why the blue food movement has brought together scientists, policymakers and communities across the globe to make aquatic food a bigger part of our diet and to reduce our reliance on land animals and cultivated fields. In other words, red meat and vegetables.

Recently, the United Nations also acknowledged that blue food can play a central role in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals in supporting healthier, more sustainable and more equitable food systems globally and in many of the most climate-challenged and food-insecure communities.

So have we really hit a jackpot? That depends on how we move forward. There’s still a lot we don’t know about blue food systems and there isn’t nearly as much research done in this area as we have in the field of land-based food production. Some crucial questions that should guide our path ahead can be: blue food has a lesser environmental footprint than its terrestrial counterpart but does that benefit remain when we scale production? How can we look at blue food as part of an integrated food system to avoid tradeoffs we would regret? How can we benefit from the incredible diversity within blue food to boost those that are less harmful to the environment?

Blue Food Assessment — a joint initiative between Stockholm and Stanford university, and EAT —is one such initiative that aims to fill in the knowledge gaps, and to inform and propel change in the policies and practices shaping the future of food.

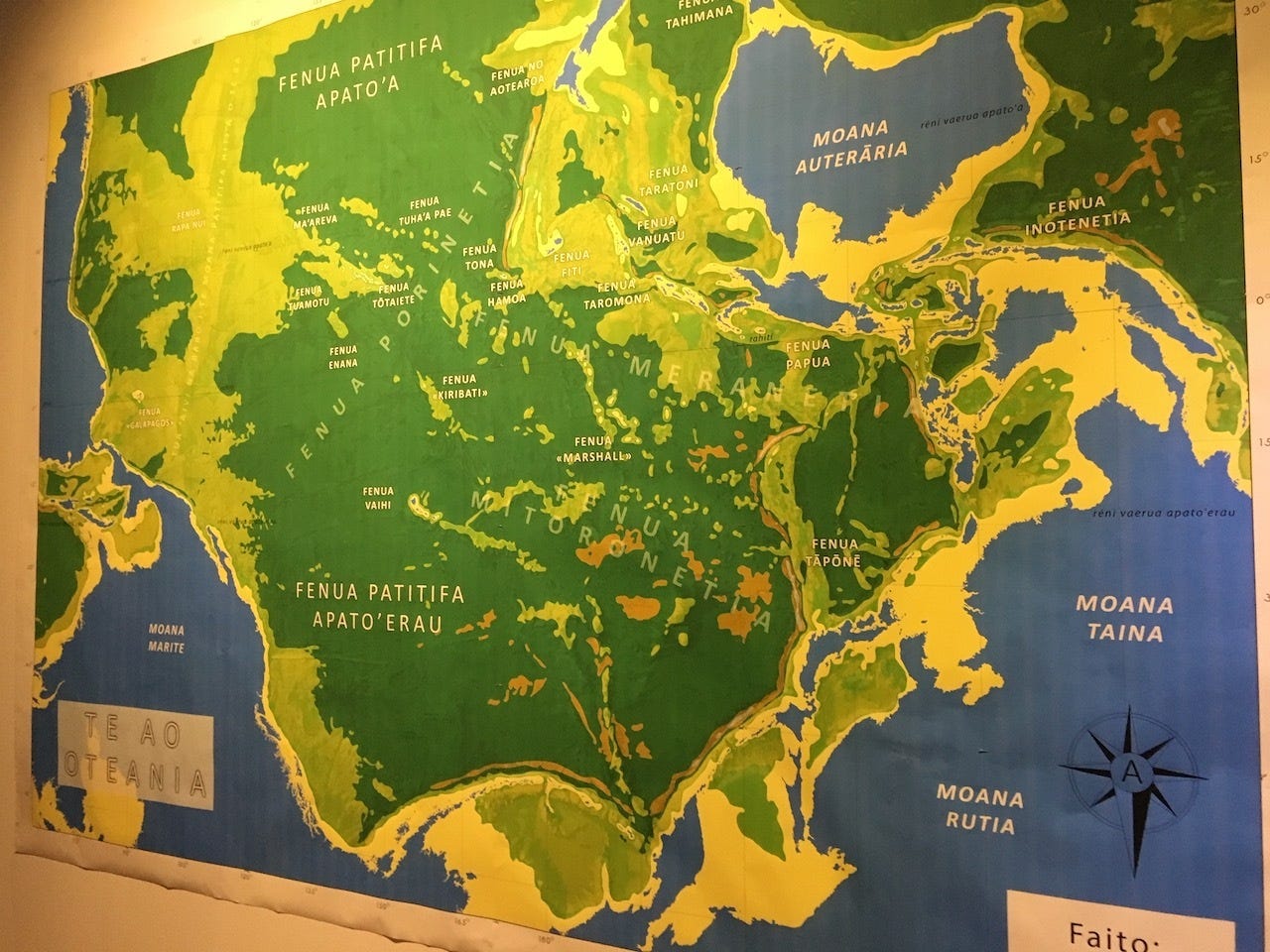

Naturally, the Pacific Island communities are best suited to fill in the knowledge gaps, and Palau is leading the charge with its recently concluded Our Ocean Conference that ended with renewed commitments to protect the Pacific Ocean. Ann Singeo, a marine researcher in Palau, explained how the practice of small-scale fisheries goes back thousands of years in the island communities, how it makes them resilient to shocks, such as the Covid-19 pandemic, and how it opens doors for fishing sectors that have always been dominated by women.

Blue food seems promising and it is being hailed as one definitive way to address malnutrition but, if there is one lesson we should learn from our past it is this: let’s not put all our eggs in one basket. Let’s not jump on the blue bandwagon without understanding the complexities of this food system and how sustainable it is for our own specific communities. Sure, Palau can harvest blue food with minimal carbon footprint given the vast ocean surrounding its land, but does Sudan’s tiny Red Sea coastline have enough blue food for its 2.5 million children under five who are suffering from malnutrition? Instead of applying one solution to this global issue, can we look more closely into our communities and find what’s the best sustainable food option for us? Maybe we’re not all blue but green or yellow?

Until next week, take care and stay safe.

Hira - Editor - The Global Tiller

Dig deeper

Microalgae are a potential alternative to traditional protein sources that often have a high impact on the environment. Might this sustainable solution to our growing nutritional needs make microalgae the food of the future?

…and now what?

Have you watched the Netflix documentary Seaspiracy? It aired while we were all locked in our homes due to Covid and watching anything and everything including this.

This documentary made a big buzz around the world and had a strong impact for many people, until we learned that neither the narrative of the documentary nor the intentions of the director were as clear as we initially thought. One major critique against the documentary was that it was looking at the issue through a very narrow, if not simplistic, perspective.

But this issue is not unique to this documentary. It’s actually something quite human, or at least modern human. We like to simplify things, we like to end up putting things in boxes and have a very black-and-white approach to everything. And if we find something new, this becomes the miracle solution for everything. It happened with oil. Electric cars were invented a long time ago but, because oil happened to be quite convenient, we put all our eggs in the same basket.

It happened to agriculture as well, in my native region of Brittany. It became so profitable to grow corn and wheat that farmers went to single-crop farming in the 50s and 60s, giving up on a more diverse, but harder-to-produce type of agriculture. Since monoculture requires an overuse of pesticides, Brittany’s beaches have been invaded by green algae since the 80s.

And this can be found in many other situations, and in many other countries. You may even think of an example in your own community, of this ability of people to tend to focus too easily on a single solution to every problem.

But, in today’s world, in such complex challenges like climate change, malnutrition, inequalities, the single solution approach doesn’t work. We need subtlety, we need flexibility and we need security. Because when you put all your eggs in the same basket and you fall, all your eggs will break. But if you put some eggs in the basket and leave others at home or give them to your colleague who’s less clumsy, you might have a chance to save some.

So one lesson we can take from the Seaspiracy debacle is that we still need to work on our mindsets and methods before implementing solutions. Otherwise, we’ll repeat the mistakes of the past, just with different victims.

What the documentary forgot is that for many places and many peoples, seafood has been a reliable and sustainable source of food for centuries. That there are still communities using proper fishing methods that do not ruin natural stock and preserve the resources.

For food as for energy and many other issues, when we think about solutions, we have to define what’s best according to our context. We need shared goals at the scale of our planet, because most challenges are now global. But sorting them out will require local contextualisation.

After all, isn’t it what culture is all about since the dawn of humankind? Aren’t cultures an adapted response of our communities according to its immediate environment? If you live on an island, like us in the Pacific, seafood is an answer for food as you’re surrounded by it. Giving it up for beef makes not much sense. If you live high up in the mountains of Bhutan, wouldn’t yak meat and milk be the most obvious choice?

As we’re reflecting all together about what to do next for the challenges to come, how about using our cultures as an inspiration? But not cultures seen as a rigid, monolithic and never-changing body of rules and imperative traditions as they’re sometimes seen, but as living, flexible and subtle bodies of what we sometime calls “common sense”, which is actually a great balance of observation, adaptation and experimentation raised to the power of repetition and perpetuation.

Philippe - Founder & CEO - Pacific Ventury