Elizabeth Holmes of Theranos sold everyone on the idea that a single drop of blood is all you need to diagnose any medical condition. As someone who shares her fear of needles and blood, I can relate to her motivations.

What’s harder to understand though is how this caricature of a Silicon Valley techie managed to extract millions from the likes of Henry Kissinger, Rupert Murdoch, the Wal-Mart family and others when her technology clearly did not match her claims. The answer lies in the wider 'fake it till you make it' culture that’s pervasive in Silicon Valley.

This week in The Global Tiller, we will dig deeper into the recently concluded fraud trial of the Theranos founder and what it tells us about the Silicon Valley culture. What does accountability look like and how can we learn to differentiate between innovation and fraud?

Holmes was only 19 years old when she founded Theranos (then called Real-Time Cures) in 2003 and, by 2014, had managed to turn it into a leading health technology company worth $10 billion. However, it all came crashing down when a Wall Street Journal report exposed the company’s struggles with its blood test technology. It revealed that the company was using regular blood testing machines and collecting vials of bloods from patients, while claiming the results came from their own machines that worked with just a single blood drop. The revelations led to FDA investigations into the company’s testing on patients and eventually culminated with the founder being found guilty of four charges of fraud.

You don’t have to look far to figure out how this self-styled Steve Jobs managed to go so far. The defence put forward during Holmes’ trial argues that her behaviour is the norm in Silicon Valley. As a defense lawyer at an Alabama law firm explained:

"Silicon Valley has thus far been famously resistant to much prosecutorial activity because its business model assumes you are going to take an aggressive, optimistic view of your product or service to attract investors. And if that product or service succeeds, you’re not a fraudster, you’re a visionary."

According to Margaret O'Mara, author of The Code: Silicon Valley and the Remaking of America:

"It's baked in to the culture. If you are a young start-up in development - with a barely existent product - a certain amount of swagger and hustle is expected and encouraged."

Treading this thin line between optimism and fraud leads to another common practice in Silicon Valley: high secrecy. Companies keep their technology secret and are so cynical of intellectual property theft that they are reluctant to share their ideas even with regulatory bodies for verification and peer review. Oftentimes, even employees and investors don’t know exactly how the technology works, and even when they do, hyper vigilance of communications and non-disclosure agreements prevent whistleblowing.

It is this very culture that illustrates why Theranos is not the only startup fraud in recent years. Juicero convinced everyone to buy its $400 juice machine when this Bloomberg report showed they could squeeze the company’s exclusive juice bag just as easily with their hands. Hampton Creek, now called Just Inc, was found to be artificially inflating customer demand by forcing its own employees to buy its egg-free mayonnaise from supermarkets. There are others who were found to be putting false labels, misrepresenting financial health and simply siphoning investor money into private accounts.

Unfortunately, Silicon Valley isn’t the only one that has cornered the market on startup scams. Russian-founded space startup, Momentus, has been fined for misleading investors. Mexican startup Yogome closed its doors after its founder was accused of fraud. And French startup Air Next promised blockchain technology to revolutionise passenger transport only to be outed as a total scam with a fake website and fake identities.

What paints a gloomy picture is how little these exposés do towards changing the 'fake it till you make it' culture. Despite the guilty sentence for Holmes, Silicon Valley investors admit they are not keen to do a lot of due diligence before investing in a startup as it is such a hot market.

One could argue that these are rich-people problems. After all, the people being scammed out of millions are those who actually have billions to part with. But as consumers of the products being pitched by these startups, this may actually be a me-and-you problem because one of us could have just as easily been misdiagnosed by a Theranos blood test. What about those startups that were never caught in time? How many of them continue to fake it without our knowledge? Who can we demand greater accountability from? How can we push for more regulation in this industry?

We’d love to hear your thoughts on this 'fake it till you make it culture' so do write back.

Until next week, take care and stay safe.

Hira - Editor - The Global Tiller

Dig deeper

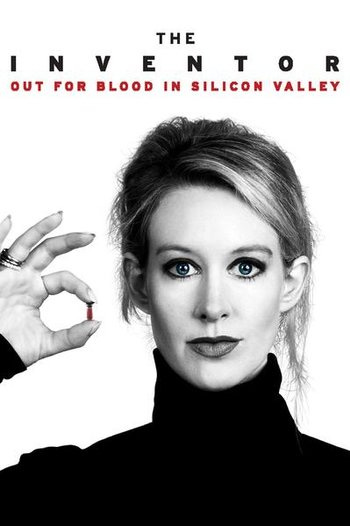

If the story of Elizabeth Holmes fascinates you, you may enjoy this HBO documentary 'The Inventor: Out for Blood in Silicon Valley'.

…and now what?

The Theranos case is an incredible story that shines light on the excesses of the tech industry, wrapped in its own cape of prophets of the future and pseudo-philosophical change-makers. Carried away by this aura, this whole industry — under its current Silicon Valley mentality — has been given a pass for many actions, decisions and projects that are now seen to be way out of line.

Elizabeth Holmes had an almost caricatural personality, complete with “I only wear one type of clothes to free my mind for more important things”. She eventually (and involuntary) pulled back the curtain and to reveal how the innovation sector is rife with issues. Mind you, she did exactly what Zuckerberg used to do. But he’s successful so that’s ok. We’re not making fun of it, we call it innovative and forward-thinking.

One could argue that it’s part of the game. You have to bet high if you want to go high. You have to be bold, a risk-taker, to have a pioneer attitude to reach for the stars. Yet the question remains, is that really what’s needed to succeed in the age of innovation?

If you look at the major figures of this world, it does seem like it: you have to be a drop-out, slightly eccentric, stubborn with good public speaking skills… All this being presented as the recipe for success, forgetting along the way that people, such as Bill Gates, Mark Zuckerberg, Elon Musk and many others were able to drop out because they were coming from very privileged backgrounds. They could afford to be bold. It was just one part of the story, one part of the myth, a well-sustained myth to maintain this aura that completely hypnotised everyone.

But there’s more to the story. It turns out that the majority of the most successful startups have been created by people in their mid-30s who have had some experience before. And I’m not only talking about Jeff Bezos but many less famous people. Most of them don’t fake much until they make it. It’s too risky. They may try to be convincing by pushing the limits of their forecasts or blurring a little bit the line between reality and their own dreams but most of them are fairly grounded professionals. Maybe that’s actually why the tech sector is still working and growing, because behind those “bigger than life” tech wizards are professionals doing the real work.

So even if the Theranos case has somehow given us the evidence of the artificiality of many elements of the startup myth, it won’t lead to many deep changes in the sector. Why?

First, as we’ve just seen, she may not be considered your typical startup founder so investors and customers may see her as a glitch more than a systemic issue

Second, because the “fake it until you make it” philosophy will still be regarded as a winning strategy as long as the sector continues to be flourishing and remain profitable to investors.

There’s another Silicon Valley’s motto that concerns me as well: “break things and move fast”. This is how major projects, such as social media platforms, have succeeded. But at what cost? The world we’re living in, the one so polarised and misinformed, is the result of this other tech guru’s motto. And it has hurt our communities deeply, all the way here, in the islands of the Pacific.

So yes, we do need more accountability, we do need more oversight. We need consumers to be part of the game, we need regulators to have a broader perspective on things. Not to limit innovation but to help it be an agent of positive change from the beginning. We should not wait for harm to happen to regulate or restrain the tech industry, or any other industry for that matter. Because the greater good is not only the sum of individual interests, it’s a deeper and wider vision and it has to be preserved and sustained for our communities to move fast and secure things: secure the basic needs for everyone, secure inclusivity and social justice, secure and sustain our environment and so on.

No project should be analysed through the eyes of the investor only. The stakeholder economy begs the same question: making sure that innovation is a source for good for everyone and not just the few lucky ones who funded it. Otherwise, as a famous innovation guru from Silicon Valley recently put it: "Nobody cares about what’s happening to the Uyghurs, ok?”. But if nobody cares about fundamental rights, is it really the kind of philosophy, mentality and leadership we want to pull humanity forward? You tell me…

Philippe - Founder - Pacific Ventury

The story of Elizabeth Holmes and Theranos is a fascinating one - I read the book "Bad Blood" by John Carreyrou and it's a compelling tale. What you say about the culture of silicon valley rings true. It's that kind of thinking - acting without thought to the consequences - that got the world into the mess it's in today. Sadly, I don't have any answers