I’d like to believe it’s the journalists who know their city best. After all, when your work involves digging around for the best stories, you’re bound to know the place, its people and how things work.

But my assumption was challenged recently when a journalist in Karachi lost her dog and didn’t know where to look. What came to her rescue were the waste pickers who knew exactly who could’ve picked it up, what they’d do to it and where it could possibly be found. Even if dog rescue isn’t part of their job description, the waste pickers seem to be running an entire underground city and are arguably our most prolific weapon in the fight against climate change.

Join us in this week’s The Global Tiller to see how waste pickers across the world play an essential role in waste management yet remain largely unseen. How can their rights be addressed to ensure a just transition towards a sustainable future?

Waste pickers, or garbage collectors, are those who make a living collecting, sorting, recycling and selling materials that someone else has thrown away. They can be formal (such as the municipal workers who drive around their trucks every night to empty out your trash bins) or informal ones (such as those who rummage through landfill sites).

It is mostly the latter that form the backbone of the recycling industry in most of the developing world. Yet, it wasn’t until 2008 that the term "waste picker" was adopted. Until then, these workers were often referred to in derogatory terms, such as 'scavengers' and 'reclaimers' or 'bagerezi' in South Africa or 'catadores' in Portuguese.

While recognition for their contributions is growing in some places, they often face low social status, deplorable living and working conditions, and get little support from local governments. Increasingly, they face challenges due to competition for lucrative waste from powerful corporate entities. Most often, waste pickers belong to extremely low-income groups, Scheduled Castes, or they are migrants with little to no formal education.

Despite being the wretched of the earth, waste pickers contribute not only to the economy but, far more importantly, to saving our environment. According to wiego.org, waste pickers collect 58% of plastics, thus contributing significantly to supplying the value chain and avoiding plastic pollution. A 2007 study found that waste pickers recovered approximately 20% of all waste material in three of six cities studied. The study found that more than 80,000 people were responsible for recycling about 3 million tons per year of waste across the six cities. It is no wonder that even Coca Cola, the highest plastic polluter in the world, is working with 5,000 waste pickers in Nigeria as part of its recycling CSR.

Besides multinationals, governments are also working with waste pickers to improve their waste management practices. Belo Horizonte in Brazil showed the way when it integrated informal waste pickers into the city’s waste collection system, followed more recently by the City of Johannesburg. Moreover, Chilean activist Soledad Mella has succeeded in getting the UN Environment Assembly in Nairobi to recognise the significant contribution of waste pickers in combatting plastic pollution.

As the global dialogue on climate change moves ahead, it is important to recognise the rights and contributions of this global hidden workforce. What steps should be taken to regulate their work? Is it enough to provide proper protective gear, or shall they be brought into the formal economy and given social security services? These workers suffer just as much from broader global events, such as inflation and the Covid-19 pandemic. How can we make sure they are accounted for in government stimulus packages as well. As Fiji recognises the local expertise needed to tackle recycling issues, how can we value our own local coalitions of waste pickers — and not only when we lose our dogs?

Until next week, take care and stay safe.

Hira - Editor - The Global Tiller

Dig deeper

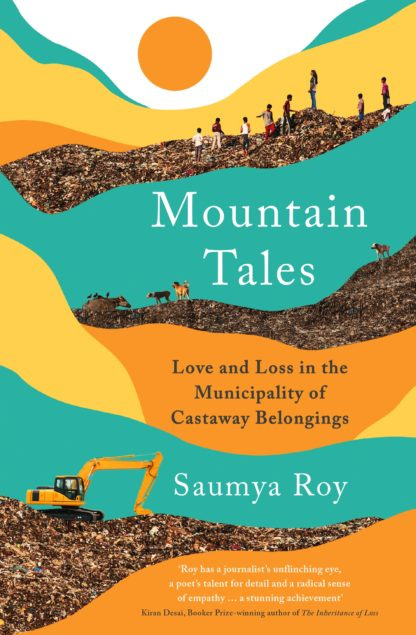

In her debut book Mountain Tales, Love and Loss in the Municipality of Castaway Belongings, author Saumya Roy follows the lives of a few ragpickers, including Farzana Sheikh in Deonar, a rubbish dump in Mumbai and one of the largest in India.

Roy speaks to Al Jazeera about the book as well as how Indians consume things today and the impact of that on waste disposal and the lives of the people dealing with that.

Find the book here.

Lord Fusitu'a on Blockchain, Cryptocurrencies and their role in the future of the Pacific - Part 3

Don’t miss our latest Pacific Toks podcast episode with Lord Fusitu’a, a Tongan politician and noble of the Kingdom of Tonga, who serves in multiple organisations and who is also a notorious bitcoin advocate in the Pacific. Our conversation has been fascinating and extensive as we delved deep into the challenges and benefits of cryptocurrencies and blockchain in the Pacific.

This is the last part of our conversation during which we discuss NFTs and their role in land management in the Pacific, as well as how we can envision those technologies as positive disruptors of our institutions, in the context of the Polynesian culture.

…and now what?

In our well-organised world (for those who have the privilege to live in developed communities and are mostly facing first-world problems), things are quite easy: open the tap, here comes water; wait along the road, here comes a bus; need to get rid of something, here’s a bin.

Things are so easy that eventually we tend to forget how everything is interconnected and that, as the French physicist Lavoisier told us, “nothing gets lost, nothing gets created, everything is just transformed."

So yes, when you open the tap there is water coming out because a complex system of pipes has been built and is managed every single second of the day. When you wait for a bus, there are complex calculations that have been done to make sure buses are coming at regular intervals and have a route that will take you efficiently to wherever you want to go.

But sometimes, in some places, like an island in the Pacific (even one considered developed, such as Tahiti) you suddenly have a glimpse of how the world works in reality. If you live up in the mountains, like my parents, you experience a sudden water shortage because the pumps collapse or the tanks haven’t been controlled and are now empty. If you wait for a bus, you might as well pray to a divinity as your next bus is trapped in an unescapable traffic that happens when there’s only one road to go everywhere.

Suddenly you realise that nothing is simple. Things have been made simple for you to feel a smooth daily life. But this luxury of simplicity comes at some cost for people.

The waste pickers are human reminders that our world is not simple, that our deeds have consequences and that the value that we give (or not) to things around us is highly dependent on our context. And if we never pay attention to those invisible people who help us feel better because they do the hard work after we threw our bottle in a recycle bin, then we cannot even fathom, let alone understand, why is it that our world is struggling right now.

Reading these stories tells us that, beyond the veil of comfort, there’s a harsher reality for so many of our brother and sister humans. To a point where sometimes they say enough, like China did when it stopped accepting trash from “developed" countries a few years back.

As our world faces so many existential challenges now, I struggle to see how so many of us are holding on to these simplicities of life (and, as a matter of fact, a simplistic vision of the world). How can we not look at what it takes for our world to be this way and, eventually, what it would take for our world to change for good?

Like the canaries in the coal mine, the waste pickers of the world are calling us out: Should we limit ourselves to the simplicity of a recycling system that is not as clean and efficient (especially, if we consider the toll it takes on certain human lives)? Should we continue to ignore the interconnections, the complexities and the many many layers that every single daily action entails?

Our answer should be: no, of course not! But now comes the hard part. We all know their stories but are we able to connect empathically with them? Or are we yet too insensitive to their situation as they live beyond an artificial border and they don’t “look” like us?

Solving our challenges and getting our world ready for tomorrow will require us to refuse our old habits, reuse our sense of humanity and upcycle our abilities to care for one another. Otherwise, we will all end up waste picking.

Philippe - Founder & CEO - Pacific Ventury