When I really enjoy a book, it is quite difficult for me to physically let it go. So I read the reviews on the cover, the author’s note, the publisher’s note, any excerpts from other books printed by the same publishers. If there is even a single page printed after the end of the novel, I will read it until I am prepared to part with the book. It was during one particularly difficult goodbye that I read the story of Penguin publishers:

Penguin Books was originally founded in the UK in 1935 by Allen Lane, who envisioned a collection of quality, attractive books affordable enough to be “bought as easily and casually as a packet of cigarettes.”

"What a noble idea!" I thought, minus the cigarettes reference, of course. Fast forward to 2020. Penguin, which had already acquired its closest competitor Random House, bought its next competitor, Simon & Schuster for $2 billion, consolidating the publishing industry into a monopoly. Not so noble anymore, eh?

These recent developments are a cause for concern so this week, in The Global Tiller, we take a closer look at what’s happening to the publishing industry, what are some existing structural faults and what could be the future of storytelling.

What’s happening in the book publishing industry comes in the larger context of Amazon’s monopoly over retail, increased manifold by the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic. To counter the influence that Amazon has over which books are sold and how they are promoted, book publishers are forming their own monopoly. How this impacts this industry is best summarised here:

As book publishing consolidates, the author tends to lose—and, therefore, so does the life of the mind. With diminished competition to sign writers, the size of advances is likely to shrink, making it harder for authors to justify the time required to produce a lengthy work. In becoming a leviathan, the business becomes ever more corporate. Publishing may lose its sense of higher purpose. The bean counters who rule over sprawling businesses will tend to treat books as just another commodity. Publishers will grow hesitant to take risks on new authors and new ideas. Like the movie industry, they will prefer sequels and established stars. What’s worse, a giant corporation starts to worry about the prospect of regulators messing with its well-being, a condition that tends to induce political caution in deciding which writers to publish.

These are troubling consequences for an industry which was far from perfect to begin with. There is a glaring racial divide in publishing revealed by the #publishingpaidme protest where writers shared how much publishing houses paid them. Established black writers, such as Jesmyn Ward, only received $25,000 for her award-winning novel Salvage the Bones while Chip Cheek, a white male author, received $800,000 for his debut novel Cape May. In fact, just 11% of books in 2018 were written by people of colour.

The problem is hardly confined to the English-speaking world. The French publishing industry has also come under harsh scrutiny recently when an editor was caught in a scheme to hand a prestigious literary prize to a pedophile writer, an event that has raised a broader discussion on an insulated, out-of-touch literary elite used to operating above ordinary rules.

For their part, Chinese censors are targeting German publishers and preventing them from translating books that are critical of the Chinese Communist Party while pushing hard on regime-friendly authors to tell the Chinese story, the right way. Of course, restricting which books get published is not a new phenomenon judging by the fact that thousands of people celebrate Banned Books Week every year.

For all the hot takes around free speech, it makes one wonder where the future of storytelling and knowledge will be. Are we going to be silenced by authoritarian governments keen on suppressing dissent, or will we only have the option to read certain kinds of books because they will, after all, be published by one company? Will publishing houses decline more and more right-wing writers, such as US senator Josh Hawley, when they had been publishing similar fact-free rhetoric for a handsome profit until now? How diverse will author pools be if the industry continues to drive independent publishers out of business?

Until the inevitable happens, I’m taking some comfort that my bookshelf is not completely taken over by penguins 🐧 yet. How many penguins do you have on yours?

We’d love to hear your thoughts too, so do write back.

Until next week, happy reading!

Hira - Editor - The Global Tiller

Want to read more about books?

For this bookseller of Kabul, the pandemic was a blip in a country afflicted by long-term war

Washington’s Secret to the Perfect Zoom Bookshelf? Buy It Wholesale

…and now what?

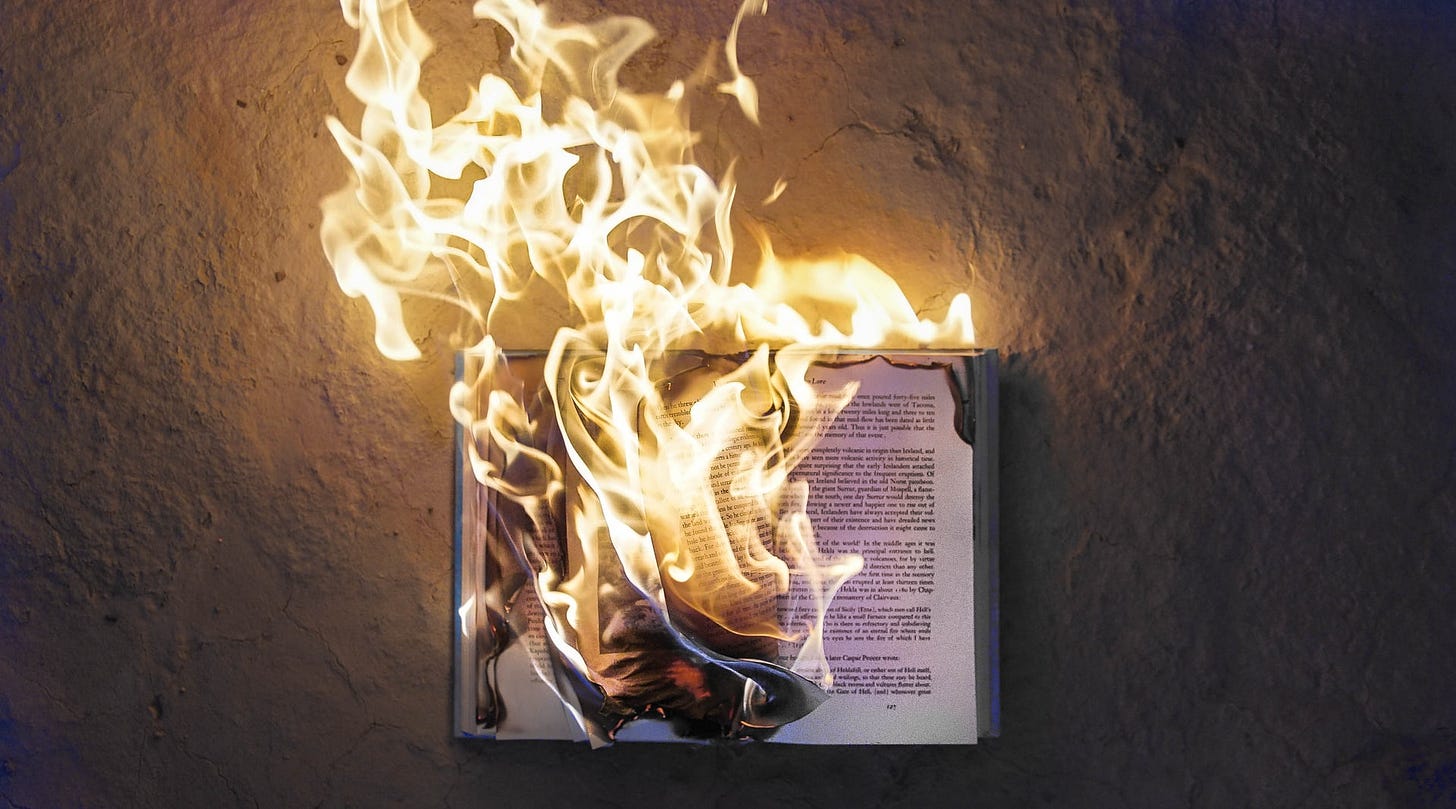

“It was a pleasure to burn."

If you know your sci-fi classics, you’d recognise this as the first sentence of Ray Bradbury’s famous Fahrenheit 451. Troubled by Nazi book burnings, Bradbury was envisioning a world where books were as illegal as drugs.

But looking at what’s happening today, we may not even have to burn them. They may just be crushed between monopolies and trend-of-the-time authoritarian governments!

The irony in all this is that at the same time that the publishing industry is becoming a new monopoly without much public knowledge, Big Tech is under high scrutiny for the same reasons. As if monopolies were an important to monitor only for trendy issues and not for old innovations.

Facing this paradox, there are two ways to think about it:

To focus on the Big Tech monopolies instead of the publishing industry, considering that knowledge mostly accessible online now.

Or, preventing anyone from having overpowering control over both mediums, considering that both are bearer of humanity’s knowledge no matter the medium used to store and share it.

The current debate on freedom of speech on social media is similar. Who gets to decide who can say what? The same goes for the monopoly issues: who gets to decide what’s worthy of being recorded for the sake of humanity’s knowledge?

I don’t see any difference between China censoring books or an almighty monopolistic publisher deciding who’ll get published. As much as I don’t see any difference between China monitoring my data or Facebook doing it. I trust neither of them. And I’d like to have a say in it. Thank you very much.

We can go back even further looking at this issue. There was a time when one dominant culture thought that it has to be preserved while other cultures could disappear because of arbitrary, subjective rankings. This happened to my native culture whose remains are now stored on the “folklore” shelves in bookstores or on Wikipedia.

Anyway, I’m getting lost in my thoughts here. I should maybe grab a book or find a website that’ll provide me some grounded knowledge on the issue. Oh yes, but know I don’t know anymore if I can trust them because the diversity that once existed is no longer guaranteed.

So what should we do today in order to make sure that any kind of knowledge, “absolute and relative” to quote the French sci-fi writer Bernard Werber, is preserved? Because eventually, who is to judge what’s worthy to be published, uploaded or archived?

Monopolies are not wrong just because of economic questions. They’re bad because they allow a few to have a huge power over everyone. The antithesis of democracy. The antithesis of openness and inclusion. The antithesis of our shared humanity: diversity.

So if you share the same approach, if you consider that every idea could one day prove worthy of being seen, read, shared, discussed, then remember these wise words from Bradbury:

I saw the way things were going, a long time back. I said nothing. I’m one of the innocents who could have spoken up and out when non one would listen to the ‘guilty’, but I did not speak (…). Now it’s too late.

Knowledge, perspectives, ideas and thoughts are our most precious goods. Let’s make sure they’re shared and preserved for the sake of all, not for the shares of some.

Philippe - Founder - Pacific Ventury