Where am AI?

Issue 95 - 12 April 2022 (8-min read)

It’s been a while since we’ve been hearing warnings of computers taking over but I’ll still have to cook my own dinner tonight, so I guess they aren’t here yet.

This week in The Global Tiller, we check in on artificial intelligence and see how far it has come along. What is it capable of and what are some areas where it’s still defeated by humans? We also look at the urgent conversations that need to happen as AI technology improves enough that computers are actually able to cook our dinners at home.

According to the Artificial Intelligence Index Report 2022, AI is starting to be deployed widely into the economy with major investments taking place in the sector. In 2021, $96.5 billion was invested in the private investment of AI and AI-related startups, which is 103% more than the investment in 2020. New Zealand, Hong Kong, Ireland, Luxembourg, and Sweden are regions with the highest growth in AI hiring from 2016 to 2021 and these trends are likely to continue in the coming years.

As a result, AI is becoming more affordable and higher performing. Since 2018, the cost to train an image classification system has decreased by 63.6%, while training times have improved by 94.4%. This efficiency is mostly recorded in categories, such as recommendation (think of autocorrect), object detection (think of Snapchat filters and self-driving cars) and language processing (think of Google Translate or DeepL).

Naturally, this means that AI is becoming more commercially viable and there will be more widespread adoption. We can see just how far the technology has reached in this video of a self-driving car stopped by the San Francisco police. After the initial stop in the middle of the road, the car actually drives a little further to find a safe spot to park and allow the police to continue their fruitless questioning of no one.

The report also states that the number of newly funded AI companies continues to drop, from 1,051 in 2019 to 746 in 2021 meaning that the investment is becoming increasingly concentrated among a few companies. If social media is any indication, enabling a monopoly in AI manufacturing may not bode well for our societies.

Perhaps we can take comfort in the fact that there is more global legislation on AI than ever. An AI Index analysis of legislative records in 25 countries shows that the number of bills containing “artificial intelligence” that were passed into law grew from just 1 in 2016 to 18 in 2021. Spain, the United Kingdom, and the United States passed the highest number of AI-related bills in 2021 with each adopting three.

The report also unveils an unlikely friendship between the US and China. The collaboration between the two countries has increased by five times since 2010 and has produced 2.7 times more publications than between the United Kingdom and China—the second highest on the list.

However, a worrying trend that continues is that of biases. The systems are growing significantly more capable over time, though as they increase in capabilities, so does the potential severity of their biases. These often take the form of sexist hiring practices, racist criminology scores or discriminatory credit ratings.

Fortunately, as the report notes, the ethical issues associated with AI are becoming more magnified as well, and research on fairness and transparency in AI has had a five-fold increase since 2014. But even if AI is being deployed globally — contributing to a broader set of AI systems for people to use and a reduction in their prices — ethical checks are mostly restricted to English-language systems and datasets. For the moment, any AI development taking place in another language is bypassing oversight.

One area in which AI has still not been able to exceed humans is in complex language tasks, such as abductive natural language inference — our ability to infer the most plausible explanation. For example, if Jenny finds her house in a mess when she returns from work, and remembers that she left a window open, she can hypothesise that a thief broke into her house and caused the mess, as the most plausible explanation. The difference is narrowing and AI will likely catch up to humans on this soon.

AI may not be turning on the stove for my dinner tonight but it will be recommending the recipe I’ll cook, translating the ingredients and labelling the photos I’ll take to generate another 'Tasty Bites' video montage of dinners over the years.

Since AI is projected to take over our lives even further than it has now, the ethical concerns around the biases it perpetuates must remain at the heart of all conversations. Universities may be crawling with computer studies students but we have to make sure the incoming cohorts includes women and people of all ethnic backgrounds.

As we adapt to this new presence in our lives, let’s question how much carbon footprint does AI manufacturing actually entail? Are our policymakers focusing on making AI more inclusive, or are they pocketing cash from lobbyists pushing for a free reign? For that matter, are our politicians even paying attention to AI at all?

Until next week, take care and stay safe.

Hira - Editor - The Global Tiller

Dig deeper

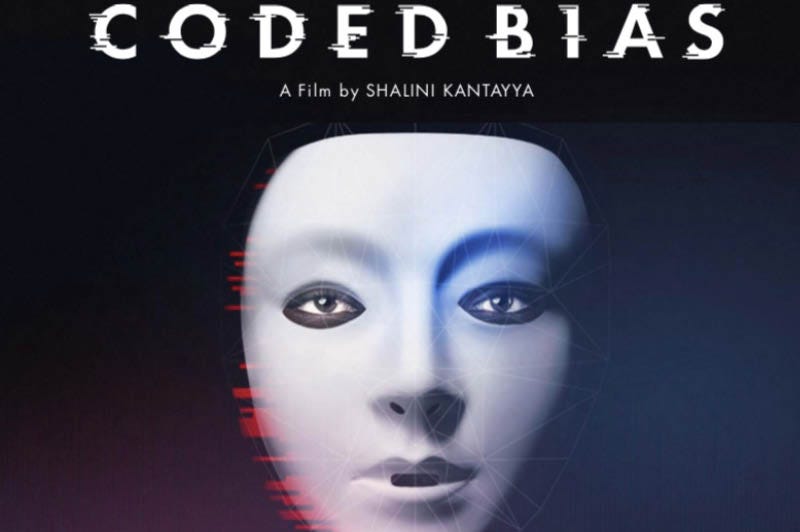

CODED BIAS explores the fallout of MIT Media Lab researcher Joy Buolamwini’s discovery that facial recognition does not see dark-skinned faces accurately, and her journey to push for the first-ever legislation in the US to govern against bias in the algorithms that impact us all.

…and now what?

I’ve learned recently that Cleopatra lived closer to the time of the iPhone than to the time when the pyramids were built. You realise that the appreciation of time is difficult when you take a step back from current events and, sometimes, we miss easily the speed of changes to come.

For many people today, AI is still a thing of the future. They envision it as this smart speaking computer, a kind of know-it-all, do-it-all, annoying persona bracing to take over the world. To all those people, I have bad news. AI is within this computer I’m typing on, within the smart phone that sits on my desk, within the smartwatch on my wrist and within my TV as I watch Netflix. Basically, everywhere! It’s so present in our daily lives that people are complaining about how AI impacts the pictures that we take.

Nevertheless, AI still remains a vague concept in our everyday consciousness, especially when you’re living on a Pacific Island where all this seems far away.

So how do we get people on board with this topic? How can we raise awareness so we don’t get people adapting to it when it becomes too late, when adaptation will require sacrifices, when it would have already risen inequalities?

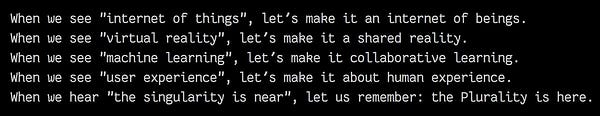

This is a tough challenge, not only when it comes to AI but for all other existential challenges facing us. But the question needs to be asked: how do we make sure people are focusing on this challenge so they can find ways to make the most of it? Because at this stage, it’s no longer about discussing the possibility that it may come and whether or not we’ll accept it, it’s about how do we live with it. Should we compete? If so, I’m afraid the game may be lost already. Are we learning to cooperate? In that case, I believe lies our best abilities. Because humans are champions of cooperation, among themselves but with other species too. We’ve been doing this with animals since a long time, so why not with AI?

This would require getting people, especially within our workplaces, to understand what’s at stake. To understand that, given the pace of change, they need to act now even if it still seems quite distant.

It won’t serve anyone to ring alarm bells and sirens to make people panic but it would be better instead to help them focus on something that will encourage them to thrive, to grow, to reach for the best of themselves. People have the ability to be at their best and rise to any challenge if they feel motivated, from finding the flow in a basic task to gaining perspective by understanding the goals of the organisation, .

So within our organisations, we need to infuse a culture that’s pulling people up, that takes them on a path of perpetual improvement, not just in terms of performance but in terms of finding the best version of themselves. It’ll benefit the organisation in the short-term, and it will benefit them in the long-term when AI fully enters as a new player.

This strategy of hope through excellence has to be applied from the bottom up. Informing and training managers to step up to the challenge of AI is important but this should apply to anyone within the organisation. Being able to step up, being the one in the team who takes up initiatives, who cares about colleagues, who gets involved in side projects, in conversations and collaboration around strategy… all these are opportunities for anyone to thrive and to legitimately secure a place in the game. As we help organisations move forward in this time of increasing AI presence, we need to make sure we prepare everyone to grow to the best of their human abilities.

Whatever AI will do, however it will impact our workplaces, the major question will be about its positive disruptive impact and the level of friction it will have within the organisation. If we prepare everyone for it by taking the high road, AI will become a force for good as it will fill up a space already left by humans. If we don’t, it will be about a competition for survival, and this never ends well, neither in the movies nor in real life.

Philippe - Founder & CEO - Pacific Ventury